Precarious Life: the fate of the Hazara people in Afghanistan.

Legend has it that in the Bamiyan valley of Afghanistan, a long time ago, the Hazara community were tyrannized by a vicious double headed dragon that devoured people every day. At that time there lived a great warrior named Salsal, son of Pahlavan, who fell in love with princess Shahmama, the daughter of the Mir (ruler) of Bamiyan. Salsal asked for the Princess’ hand in marriage, but her father did not want to see her married off. He sets two conditions that could never be fulfilled by Salsal or at least would get rid of him.

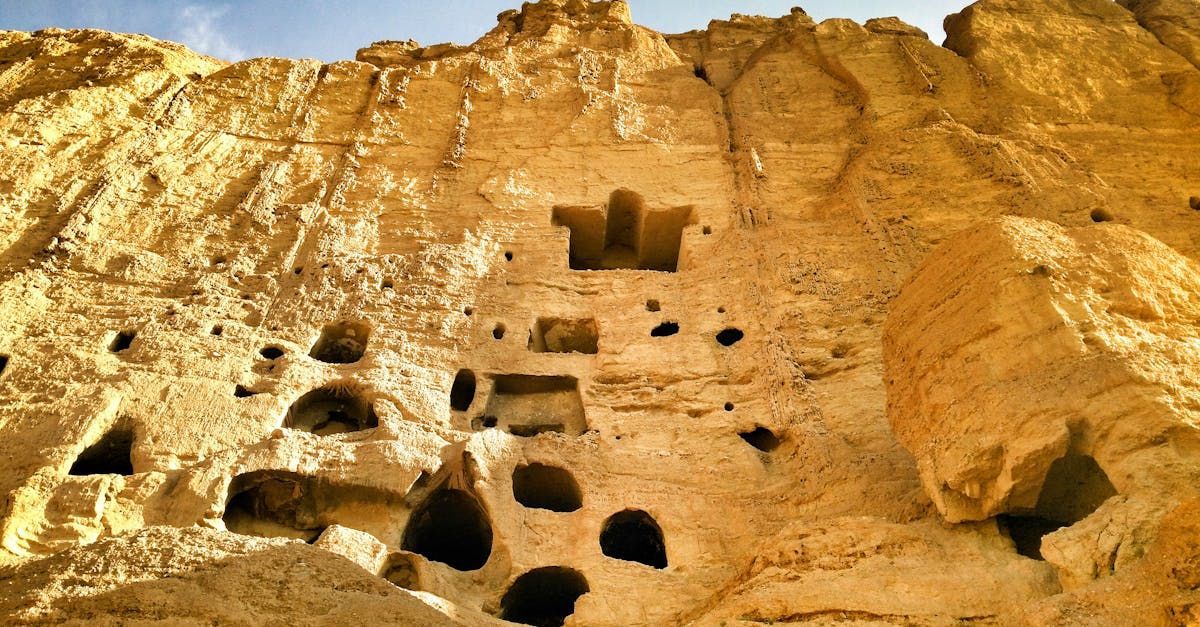

To prove himself worthy he would have to save the Bamiyan valley from its frequent flooding and kill the dragon. Salsal first needed to get steel mined at the Fuladi peak, which crowns the Baba Mountain range, a western extension of the Hindu Kush. Then he travelled to the province of Ghur to have the sword forged by a Pir, a holy man. With this legendary sword he built a dam wall to block the river, which today in Hazara tradition exists as Lake Band-e-Amir. Salsal defeated the dragon in a deadly fight and skinned the creature to be used as a carpet for the day of marriage. The Dragon rock formation, known as Darya Ajdahar, is said to be the petrified remains of the dragon.

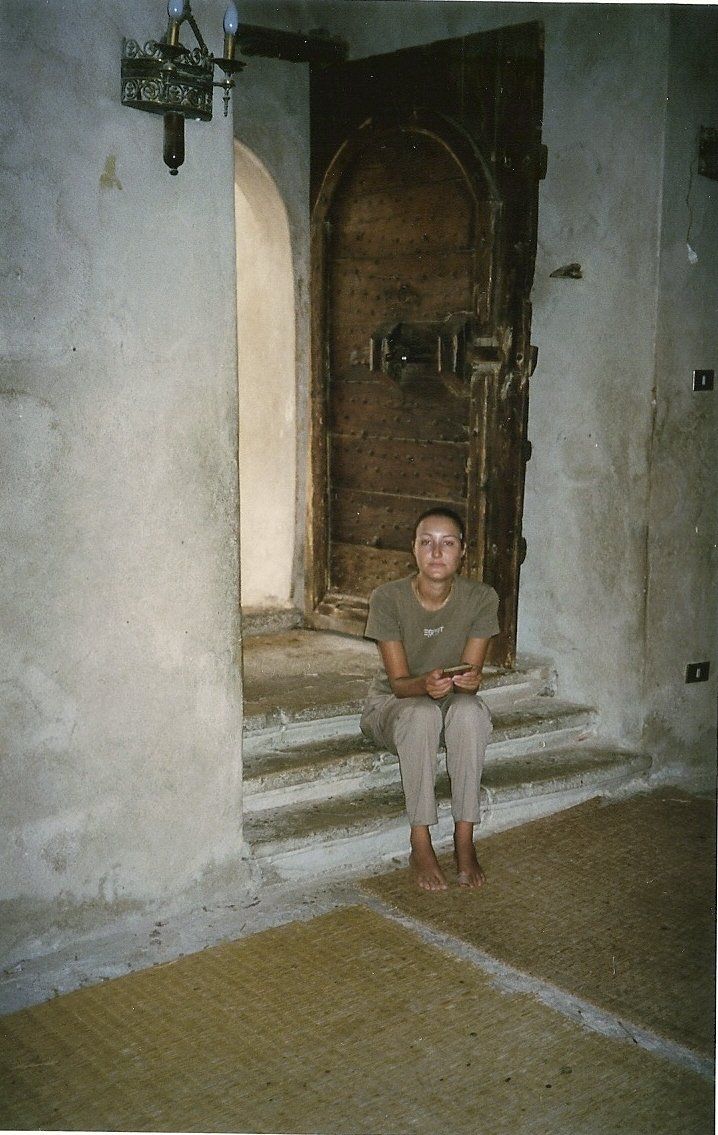

When Salsal returned to claim his bride, two niches were carved for them on the façade of the mountain, to commemorate his victories and celebrate the wedding. The ceilings of the niches were beautifully painted which gave the caves a mysterious glow. In the groom’s niche a green embroidered curtain was hang, and the bride’s niche received a beautiful red decorated curtain. The plan was that couple would spend the night each in their own cave and wake up by sunset to open the curtains. After that they would walk on the carpet made of dragon skin towards their future life.

But the triumph was short-lived, Salsal was found petrified the next morning. He had succumbed to the dragon’s poison. When Shahmama heard Salsal had died, she uttered a deadly sharp shrill sound and turned to stone. According to the Hazara legend, the two Buddhas were the petrified bodies of the lovers Salsal and Shahmama, locked in an eternal separation.

The destruction of the colossal Buddha statues of Bamiyan in Afghanistan by the Taliban triggered a tremor that could be felt throughout the world. This deliberate act of the obliteration of culture, history and identity motivated by an extremist ideology was felt at the very heart of the global community. In January 2002, UNESCO was officially requested by Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Afghan interim administration to play a role in safeguarding of all Afghanistan’s cultural heritage.

Sadly, the ties of the Hazara with the Buddhas were not emphasized in their efforts to protect Afghanistan’s heritage. The Hazara, who are primarily Shi’a Muslims, have a rich oral tradition and these ancient stories are woven around their community, where they have become an important part of Hazara’s rich folklore. The folk tales have been passed down through generations, and traditionally would have been told as an attempt to explain the world around them. The Hazaras started a campaign for the reconstruction of the statues, but this was rejected by UNESCO and the Afghan government.

The Buddhas had been central to the identity of the Hazara community for centuries. The Hazara did not built the colossal Buddhas, but the statues carried on their shoulders the ancient accounts of their ancestors. The Bamiyan valley is a central location, a point of passage in a natural movement that has been going on for millions of years, of which the Silk Road is the nearest reflection. The place where east meets west, fuses with the memories retained in the bones of the Hazara. Their heritage has been destroyed, rebuilt, re- imagined, innumerable times, but underlying these changes lies a deep, inescapable continuum, experienced just below consciousness, embedded in their traditions.

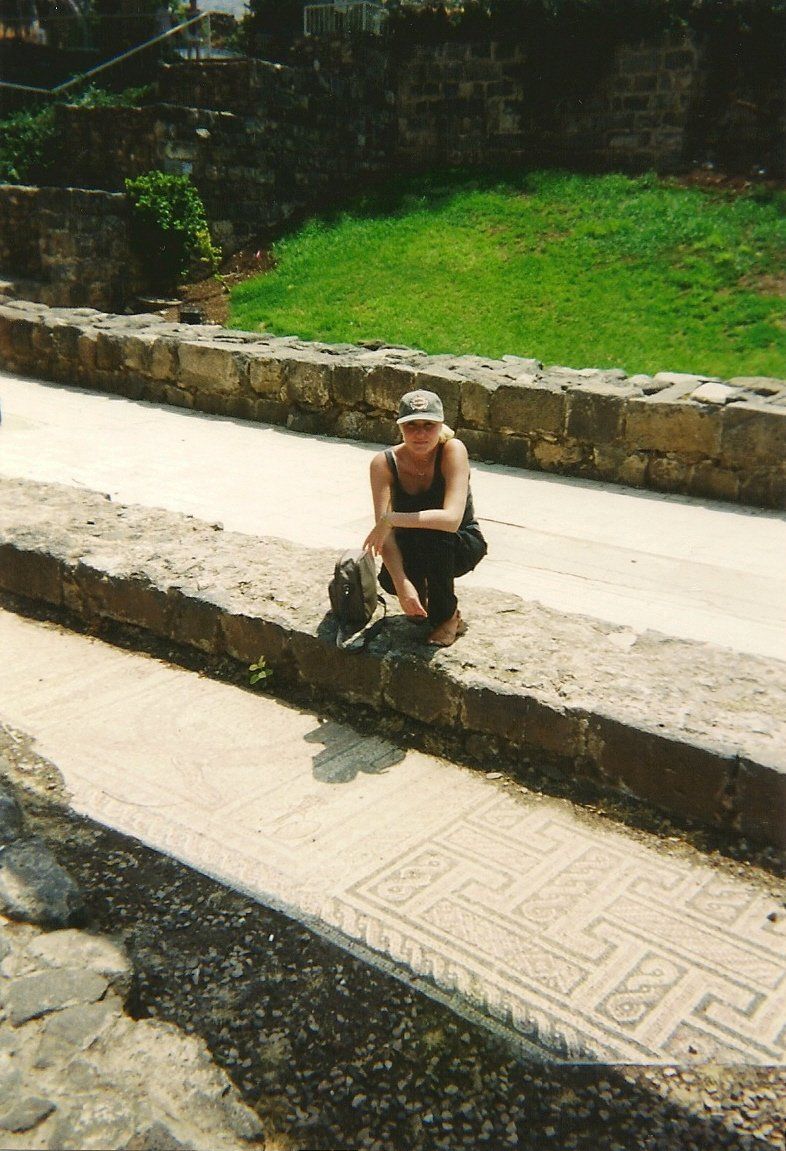

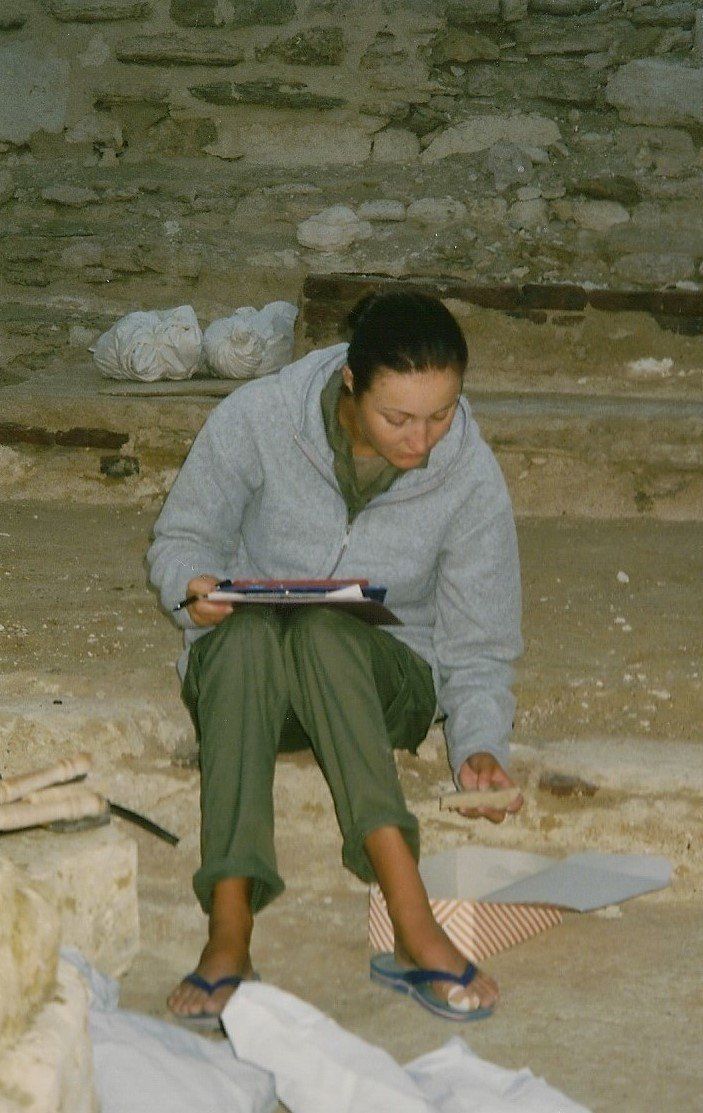

Archaeological heritage is a living being, with a memory of its own, entwined into an intimate engagement with the present. Archaeological sites age and change by the people living in its valleys and adjacent areas as does the ideological or religious importance of the living tradition. The meaning of high mountaintops, caves with subterranean lakes, or ancient Buddhist figures carved into the face of a large cliff evolve through the centuries. Haunting legends are filled with what people remember, and what they cannot forget.

Heritage reflects the complex interplay between history, memories and the present. The material form can be altered, damaged, or even destructed. But heritage never dies when the stories are kept alive. Those stories carry the meaning and significance of the material remains of the past and of a particular group of people. When the stories cease, the Hazara will cease to exist. Which is exactly the point for the Taliban. The Bamiyan Buddhas were opportunistically propagated by the Taliban as symbols of idolatry and the Hazaras were accused of blasphemy. The physical destruction of heritage gave the Taliban the power to reject the Hazara, classify them as unimportant and erase them for the future generations. Cultural cleansing went paired with killing of the Hazaras, burning their houses, and expelling them from the Valley.

The Taliban did not perceive the figures as religious icons. They had already been defaced and fallen out of worship more than a thousand years previously and the Buddhas had already been recognized by the Muslim scholars as cultural heritage. When Mullah Omar proclaimed in February 2001 to destroy “all non-Islamic statues and tombs considered offensive to Islam” the international community explained this horrendous deed as within the contexts of “Islamic Iconoclasm”.

There is an important point made by Said Reza Huseini that the faces were already removed in the medieval period and exposed to Muslim iconoclasm. From that time the religious significance came to an end, and they became cultural icons, as can be attested by the fact that no medieval Islamic text objected to the existence of these statues. Kavita Singh points out that in 1999, the same Mullah Omar had promised to protect these very Buddhas as the Buddhas were not idols under worship and there absolutely no religious reason was to attack them.

Many theories have been proposed as to why the Taliban destroyed the Buddhas and many different political processes were evolving in 2001. The Sunni Islamic intolerance towards representational arts got the most attention but we must also look at the severe economic sanctions that rested on Afghanistan. The Taliban tried to build bridges with the international community and had destroyed Afghanistan’s opium crop. The United Nations refused to recognize the Taliban regime and imposed fresh sanctions, whereas the Taliban on their side refused to surrender Osama bin Laden. Revenge against “the West” and targeted violence against the Hazara community was a strong motivation behind the destruction.

Why is it that so few have heard of the Hazara community? The Hazara had been hopeful that in 2001 they would get a better life after decades of systematic oppression and discrimination. But the challenges they faced didn’t disappear and they were still harassed, being blocked from access to electricity, essential services, and victims of targeted killings.

In the 1890s, 60 percent of the Hazara population was murdered. It makes me feel sick to my stomach every time I read or hear this. They were dispossessed of their land, displaced from their homes, men, women, and children were sold and enslaved. They were once the largest Afghan ethnic group constituting nearly 67 per cent of the total population of the state before the 19th century. And the killings continued. It was in 1998 at the city of Mazar-i-Shariff that more than 8,000 Hazaras were systematic killed in a matter of days by the Taliban. Thousands of Hazaras were abducted, tortured, or taken as prisoners. Najibullah, a refugee who found a home in Canada, recalls being transported in the tank of a truck. They had no idea where they were being taken and it was so hot in the container that many died during the journey. When they arrived, even the elderly and the children were beaten with chains and denied food for 12 days.

Today, they are still faced with a multiple headed dragon, only it is in the form of systematic ethnic and religious persecution, executed by extremist Sunni Muslims. The Hazara are usually described as a Persian-speaking people of Mongol ancestry living in the high mountains of central Afghanistan, in an area called the Hazarajat. But there have also been Hazara populations found living in west, north and south of the country.

European writers like Armenius Vambery (1864), Alexander Burnes (1839), and Mountstuart Elphinstone (1978) wrote with colonial bias that they represented the last remnants of the great Mongol dynasties that came through this area based on the notion that they could be identified by a specific set of physical features they shared with Mongols. The Hazara now speak a dialect of Persian, called Hazaragi and the name Hazara is thought to derive from the Persian word, hezar. Which means “thousand”, referring, perhaps, to a military unit in the Mongol army, but there is no historical evidence of this.

Though their origin remains controversial, most scholars agree that they are most probable a mixture of an indigenous population, with Iranian, Turk, and possibly the Mongols. The Hazaras have suffered discrimination throughout modern Afghan history and endured particularly severe persecution through the period of Taliban rule from 1996 to 2001.

Despite the intense fear and insecurity, they endure, their response to the violence and oppression has been nonviolent and they see violence as a last resort. By protests, social media activism, education, academic research, the arts, and political activism they fight against systematic ethnic discrimination. The Hazara are among the country’s poorest, often lacking basic facilities and electricity. But literacy levels are high among the Hazara, and the women have traditionally enjoyed more freedom in their society than other ethnic groups. As they seek empowerment in education, almost all girls are educated.

Prof. William Maley, leading expert on Afghanistan, warned last May that “ it is a serious mistake to conclude that Afghanistan is safe for Hazaras. The disposition of extremists to strike at them has not disappeared – and, importantly, it precedes the emergence of ‘Islamic State’ (ISIS/ISKP). This was tragically demonstrated on 6 December 2011, when a suicide bomber attacked Shiite Afghans, most of them Hazaras, at a place of commemoration in downtown Kabul during the Ashura festival that marks the anniversary of the Battle of Karbala in 680 CE”.

This statement came after the May 8 triple bombing of the Syed Al-Shahada girls’ school in Dasht-e-Barchi, a predominantly Hazara- populated area in Kabul. This bone-chilling massacre of 85 school children, primarily girls, wounding at least 147, confirmed how the presence of foreign Islamist groups have taken place with increasing regularity.

On June 8th ten mine clearance workers were shot in cold blood by masked gunmen in the northern province Baghlan, and more than a dozen were wounded. Mr. Cowan of the Halo Trust told the BBC that a group of armed men came to the camp and sought out members of the Hazara community, and then murdered them. The Islamic State group claimed the attack. The HALO group, who rose to international prominence in 1997 when Princess Diana walked through one of HALO’s minefields in Angola, employs thousands of Afghans. They began working in Afghanistan in 1988, completely Afghan-led, with an ethnically diverse workforce of over 2,600 staff, recruited directly from towns and villages affected by landmines.

Amnesty International confirmed that the Taliban brutally tortured and killed Hazara men last August in Ghazni province. Now that the Taliban has retaken control of the country, and the local Islamic State franchise, known as ISIL- Khorasan (ISIL-K) present, the Hazara face an even greater risk. The drama unfolding under our eyes is more poignant than ever. Afghanistan has been the scene of some of the most serious human rights violations on record.

The hatred of Hazara is a poison and its necessary for us to talk about this injustice. Not only is it deeply disturbing, that these serious crimes against the Hazara are already happening (again), but it also requires us to act. Education against hate speech and violence against the Hazara people should be on the Afghan and global agenda. Not only do we have to combat the harsh discrimination and suffering but we also must safeguard their cultural heritage, in a way to collectively acknowledge and remember lost history, recreate lost identity, and thereby open the way for healing this evil. The Hazara have made themselves heard. Now is the moment to get their voice heard by our government representatives. If these last few months have taught us anything, it's that we need open our eyes to the fact that the Hazaras are not safe. This not an early warning, it didn’t just happen overnight, it is going on right now.

References:

By Sajjad Askary and Sitarah Mohammadi. School Attacks on Afghanistan’s Hazaras Are Only the Beginning. The Diplomat https://thediplomat.com/2021/05/school-attacks-on-afghanistans-hazaras-are-only-the-beginning/

Grant Farr (2007). The Hazara of Central Afghanistan. In Disappearing Peoples? : Indigenous Groups and Ethnic Minorities in South and Central Asia. Routledge, 2007. Barbara Brower, & Barbara Rose Johnston.

Finbarr Barry Flood. Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum. The Art Bulletin Vol. 84, No. 4 (Dec. 2002), pp. 641-659.

Guanglin He, Atif Adnan, Allah Rakha, Hui-Yuan Yeh, Mengge Wang, Xing Zou, Jianxin Guo, Muhammad Rehman, Abulhasan Fawad, Pengyu Chen, Chuan-Chao Wang. A comprehensive exploration of the genetic legacy and forensic features of Afghanistan and Pakistan Mongolian-descent Hazara. Forensic Science International: Genetics. Volume 42, September 2019, Pages e1-e12.

Said Reza Huseini. Destruction of Bamiyan Buddhas: Taliban Iconoclasm and Hazara Response. Himalayan and Central Asian Studies Vol. 16, No. 2 April-June 2012, p. 15-50.

Melissa Kerr Chiovenda (2017). Hazara civil society activists and local, national, and international political institutions. In Shahrani, M. Nazif, ed. Identity and Politics in Modern Afghanistan: Forty Years of War and Rebellion, Bloomington &London: Indiana University Press."

Professor William Maley has published extensively on Afghan politics and the Taliban: The Afghanistan Wars. London and New York: Macmillan, 2002, 2009, 2021. What is a Refugee? New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Llewelyn Morgan (2012). The Buddhas of Bamiyan.

S.A. Mousavi (1998). The Hazaras of Afghanistan: An Historical, Cultural, Economic and Political Study, London, Curzon Press.

Kavita Singh (2015). Museums, Heritage, Culture: Into the Conflict Zone. Reinwardt Academy, Amsterdam University of the Aerts.

Amnesty International Ireland. Afghanistan: Taliban responsible for brutal massacre of Hazara men – new investigation https://www.amnesty.ie/afghanistan-taliban-afghanistan-taliban-massacre-hazara/

Australian National University. On the Return of Hazaras to Afghanistan. https://www.refugeecouncil.org.auwp-content/uploads/2021/05/Maley-Hazaras-19.5.21.pdf

Canadian Hazara Humanitarian Services (CHHS) https://canadianhazara.org/

The HALO Trust. Clearing Landmines and Saving Lives. https://www.halotrust.org/where-we-work/central-asia/afghanistan/

Human Rights Watch. Afghanistan: The Massacre in Mazar-I Sharif https://www.hrw.org/report/1998/11/01/afghanistan-massacre-mazar-i-sharif

UNESCO (2015) Keeping history alive: Safeguarding cultural heritage in post-conflict Afghanistan. Working Paper. UNESCO Office in Kabul, Paris, France / Kabul, Afghanistan, 253p. ISBN 978-92-3-100064-5.

UNHCR. Persecution and perseverance: Survival stories from the Hazara community. Jul 24, 2020 Canada. https://www.unhcr.ca/news/persecution-perseverance-survival-stories-hazara-community/

Photo wikimedia:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/carlmontgomery/3067235233/in/album-72157610407939880/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:People_of_Bamyan-5.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taller-Buddha-of-Bamiyan-before-and-after-destruction-2.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bamiyan_Site,_children,_Bamiyan,_Afghanistan.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fran%C3%A7oise_Foliot_-_Afghanistan_190.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lake_Band-e-Amir,_Afghanistan_d.jpg

https://www.flickr.com/photos/carlmontgomery/3067227655/in/album-72157610407939880/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/wentan/767716458/in/album-72157600742375669/

Blog Ticia Verveer